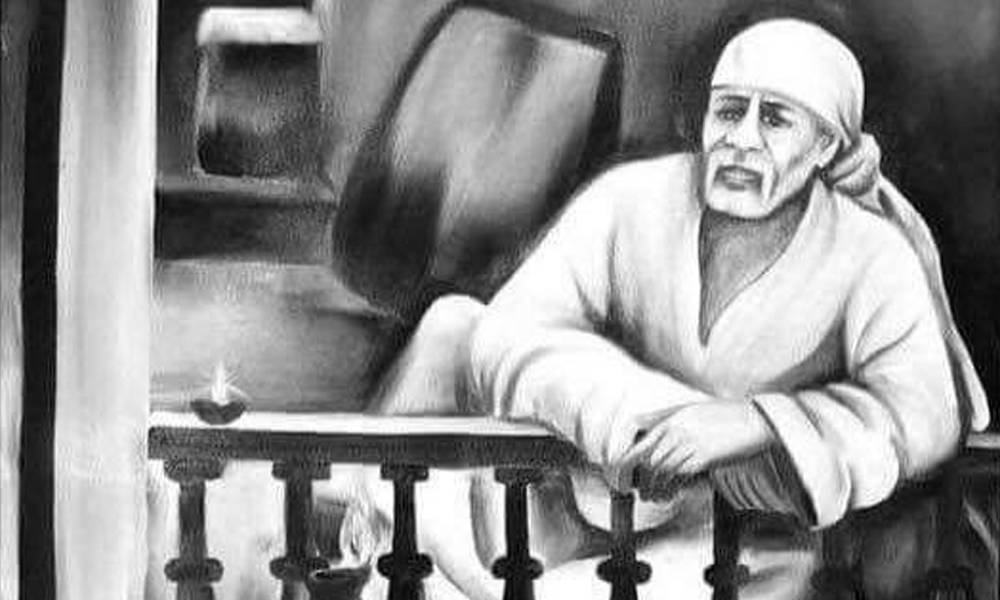

Dwarkamai

To the devotees of Sai Baba, Dwarkamai is one of the treasures. The spirit of tolerance, acceptance and welcome for all is very much alive. Baba has said that merely going inside the mosque will confer blessings, and the experiences of devotees confirm this. Sai Baba respected all religions and creeds, and all had free access to the mosque. It is typically unique of Sai Baba that he regarded a place of worship – the mosque – as a mother. He once told a visitor, “Dwarkamai is this very mosque. She makes those who ascend her steps fearless. This masjidmai is very kind. Those who come here reach their goal !”

On entering the mosque one is struck by its powerful atmosphere and the intensity and absorption with which visitors are going about their worship. Another point we notice is the great diversity of devotional expression. Some people will be kneeling before Baba’s picture of making offerings, others will be praying before the dhuni (perpetually burning sacred fire), some may be doing japa or reading from sacred texts, and others will be sitting in contemplation. If we spend some time here we may become aware of a mysterious phenomenon.

The “mayi” aspect of the masjid reveals itself in a number of ways and we feel we are sitting in Baba’s drawing room. See that child over there happily crawling around with a toffee in its mouth, or her sister colouring a comic book ? And what about the old man complaining to Baba about his aches and pains, or that woman sitting with her son on her lap telling him a story ? Opposite is a large family group. The granny has a tiffin tin, and having offered some to Baba, she walks around giving a handful of payasam (sweet rice) to everyone in the mosque. We feel we are receiving prasad almost from Baba himself, and perhaps we are then reminded of some of the stories in Baba’s life in which devotees brought offerings, or when he affectionately distributed fruit or sweets with his own hand. The atmosphere is so homely in the abode of Sai mavuli ! But what is perhaps more remarkable, is that his homeliness co-exists with a powerful experience of the sacred and transcendent. The spirit is profoundly moved by “something” – something indefinable, something great, something mysterious, something magnetically attractive. As we explore Sai Baba’s Shirdi, this aspect of Baba – at once the concerned mother and the Almighty – is shown again and again. Many devotees relate to Baba as a mother, and many as a God supreme. That these two are so perfectly synthesized in Baba – see his care for both the smallest domestic detail as well as the ultimate spiritual attainment – is perhaps the most beautiful and unique aspect of Shirdi Sai.

When Sai Baba moved into this mosque it was an abandoned and dilapidated mud structure, much smaller than the one we see today. In fact, it extended only as far as the steps and wrought iron dividers enclosing the upper section, with the rest of the area an outside courtyard. There were no iron bars around the mosque or the dhuni as there are today, and according to Hemadpant, there were “knee-deep holes and pits in the ground”! Part of the roof had collapsed and the rest was in imminent danger of following, so it was a rather hazardous place to live ! Once when Baba was sitting in the mosque, eating with a few devotees, there was a loud crack overhead. Baba immediately raised his hand and said, “Sabar, sabar,” (“Wait, wait”). The noise stopped and the group carried on with their meal, but when they got up and went out, a large piece of the roof came crashing down onto the exact spot where they had been sitting!

During Baba’s time Dwarkamai was always referred to simply as “the masjid” or mosque. The name “Dwarkamai” came into popular vogue only after Baba passed away but was first coined when a devotee once expressed a wish to make a pilgrimage to Dwarka, a town in Gujarat sacred to Krishna. Baba replied that there was no need as that very mosque was Dwarka. “Dwarka” also means “many-gated”, and “mai” means mother, hence “the many-gated mother” (and Baba did often call it the “masjid ayi”). The author of Sri Sai Satcharitra, identified another definition of Dwarka given in the Skanda Purana – a place open to all four castes of people (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras) for the realization of the four corresponding aims of human existence (i.e. moksha or liberation, dharma or righteousness, artha or wealth and kama or sensual pleasure). In fact, Baba’s mosque was open not only to all castes, but also to untouchables and those without caste.

The Dhuni is a sacrificial rite (Yadnya) on a pyre – a pious devotional act of worship to Agni (fire)

For many visitors, the dhuni is the most significant part of Dwarkamai, as it is so intimately associated with Baba. The dhuni is the sacred, perpetually burning fire that Baba built and which has been maintained ever since, though today the fire is much bigger and is enclosed behind a wire cage. Yadnya produces ash which is the purest substance on earth and has the power to destroy whatever evil and impure. Baba very generously distributed Udi to His devotees for protecting them from maladies.

The maintenance of a dhuni is important in several traditions, including Zoroastrianism, Sufism and Hinduism (especially the Nath sect). Fire was also important to Baba, as wherever he stayed – whether under the neem tree, in the forest, or in the mosque – he always kept a dhuni. Baba, however, was not bound by any convention or set rules, nor did he worship the fire. He simply maintained it, using it for his own particular and mysterious purposes. There were no classic restrictions around Baba’s dhuni. Baba did not prevent others from touching it – indeed, villagers would sometimes come to take embers with which to kindle their own household fires, and whenever Radhakrishnayi used to thoroughly clean and whitewash the mosque at festival times, she would move the dhuni into the street outside. Baba did not confine himself to burning only wood on the dhuni, but would throw his old clothes on it once they were worn out, and he would adjust the fire with his foot (in Indian culture it is considered disrespectful to touch or point to anything with the foot). One day, the fire in the mosque got wildly out of control, with flames leaping up to the roof. None of those present with Baba dared say anything to him but they were nervous. Baba responded to their uneasiness, not by prayer or supplication, but by magisterially rapping his satka (stick) against a pillar and ordering the flames to come down and be calm. At each stroke the flames diminished and the fire was soon restored to normal.

When Baba returned from his morning begging-rounds with a cloth bag of food and a tin pot of liquids, he would first offer some of it at the dhuni before taking any himself. We may not be able to discern exactly why or how Baba used the dhuni, but it is evident that despite the apparent informality around it, the fire was an important part of his routine. According to the Sri Sai Satcharitra, the fire symbolized and facilitated purification and was the focus of oblations, where Baba would intercede on behalf of his devotees. Once when Baba was asked why he had a fire, he replied that it was for burning our sins, or karma. It is reported that Baba would spend hours sitting in contemplation by the dhuni, facing south, especially early in the morning after getting up and again at sunset. Mrs. Tarkhad, who had Baba’s darshan regularly, says that at these times “He would wave his arms and fingers about, making gestures which conveyed no meaning to the onlookers and saying “Haq” which means God.”

Today the dhuni is maintained in a carefully designed structure lined with special fire-bricks, in the same place that Baba used to have it. Baba made an intriguing comment about this spot, saying that it was the burial place of one Muzafar Shah, a well-to-do landowner, with whom he once lived and for whom he had cooked. This is recorded in Charter & Sayings of Sri Sai Baba, but as so frequently when Baba speaks about his personal history, we do not know to which life he was referring.

From the earliest days, Baba would give udi – holy ash from the dhuni – to his visitors. The healing power of Baba’s udi is well documented and there are numerous cases of people being healed of pain or sickness by taking Baba’s udi both before and since his mahasamadhi.

Baba would sometimes apply udi to his devotees when they arrived, or when they were taking leave of him, and he often gave out handfuls of it which he scooped up from the dhuni. The Sri Sai Satcharitra tells us that “when Baba was in a good mood” he sometimes used to sing about udi “in a tuneful voice and with great joy” : “Sri Ram has come, Oh he has come during his wanderings and he has brought bags full of udi.” Udi is still collected from the fire for distribution. Since this is a continuation of Baba’s own practice, and the udi comes from the very fire that Baba himself lit and tended, it is considered extremely sacred. Today a small tray of udi is kept for visitors near the steps.

For devotees of Sai Baba there is an emotional attachment to udi as a tangible form of Baba’s blessings, a vehicle for Baba’s grace and a link to Baba himself. People usually put it on the forehead and/or in the mouth.

Baba used to beg for his food at least twice a day. He generally visited only five houses – those of Vaman Gondkar, Vaman Sakharam Shelke, Bayajabai and Ganapat Kote Patil (Tatya’s parents), Bayaji Appa Kote Patil and Nandaram Marwadi – and stand outside them calling for alms. Baba would collect the solid food in a cloth bag and any liquid offerings in a small tin pot. When he returned to the mosque he would offer some at the dhuni, then empty it all into a kolamba and leave it available for any person or creature to take from, before eating a small quantity himself. In continuation of this tradition, a kolamba is still kept here beside the water pot. People leave naivedya (food offerings) here as a gesture of offering bhiksha to Baba, and take it as his prasad. As Baba used to keep one or two water pots by the dhuni (for drinking and performing ablutions), this tradition is also maintained. Devotees like to take the water as a symbol of Baba’s teerth (holy water).

“One morning, Sai Baba was at his mosque. I was surprised to find him making preparations for grinding an extraordinary quantity of wheat. After arranging a gunny sack on the floor he placed a hand-operated flour mill on it and, rolling up the sleeves of his obe, he started grinding the wheat. I wondered at this, as I knew that Baba owned nothing, stored nothing and lived on alms. Others who had come to see him wondered about this too, but nobody had the temerity to ask any questions.

As the news spread through the village, more and more men and women collected at the mosque to find out what was going on. Four of the women in the watching crowd forced their way through and, pushing Baba aside, grabbed the handle of the flour mill. Baba was enraged by such officiousness, but as the women raised their voices in devotional songs, their love and regard for him became so evident that Baba forgot his anger and smiled.

As the women worked, they too wondered what Baba intended doing with such an enormous quantity of flour... They concluded that Baba, being the kind of man he was, would probably distribute the flour between the four of them… When their work was done, they divided the flour into four portions, and each of them started to take away what she considered her share.

“Ladies, have you gone mad!” Baba shouted. “Whose property are you looting? Your father’s? Have I borrowed any wheat from you ? What gives you the right to take this flour away ?”

“Now listen to me,” he continued in a calmer tone, as the women stood dumbfounded before him. “Take this flour and sprinkle it along the village boundaries.”

The four women, who were feeling thoroughly embarrassed by this time, whispered among themselves for a few moments, and then set out in different directions to carry out Baba’s instructions.

Since I was witness to this incident, I was naturally curious as to what it signified, and I questioned several people in Shirdi about it. I was told that there was a cholera epidemic in the village, and this was Baba’s antidote to it ? It was not the grains of wheat which had been put through the mill but cholera itself which had been crushed by Sai Baba, and cast out from the village of Shirdi.

To this day, a grinding stone is kept in the mosque with a sack of wheat beside it, as it was in Baba’s time. This tradition goes back many years to the time when two devotees – a farmer (Balaji Patil Nevaskar) and his landowner – came to Baba for arbitration. Although Nevaskar had been cultivating the land for decades, the owner wanted it back. Baba advised him to comply with the owner’s wishes, but instead of giving the crop to the owner he sent the whole of it to Baba, keeping none for himself ? Baba took a small portion of it, which he kept beside him all year, and returned the rest. In this way the custom was born and the ritual was repeated every year. These days a bag of wheat is kept in a glass case by the grinding stone throughout the year, and is replaced annually on the festival of Ramnavami.

Sai Baba Temple

Gurusthan

Dwarkamai

Chavadi

Sai 9 Thursday VRAT

Sai Baba 11 Assurances

Annadhanam (Free Prasad Bhojan)

During Weddings, Birthdays and Special Occasions, make a sacred offering of food, which will provide sustenance for worshippers in the Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust.

In honor of your ancestors, make a sacred offering of food, which will provide sustenance for worshippers in the Shri Saibaba Sansthan Trust.

Subscribe

Subscribe